How I think about Product Management

Product management is fundamentally about trying to please everyone and then realizing you cannot. I spent my college years working out utility maximization equations with the underlying assumption that people behave rationally. Back then, I thought it was clear that this was merely an assumption, but this didn’t really hit me until I started working in product.

I started seeing irrational actors everywhere. People doing things inefficiently simply because that’s what they’re used to. People not switching to a new time-saving software because they don’t have “time” to learn. An executive demanding a random feature without using the product themselves.

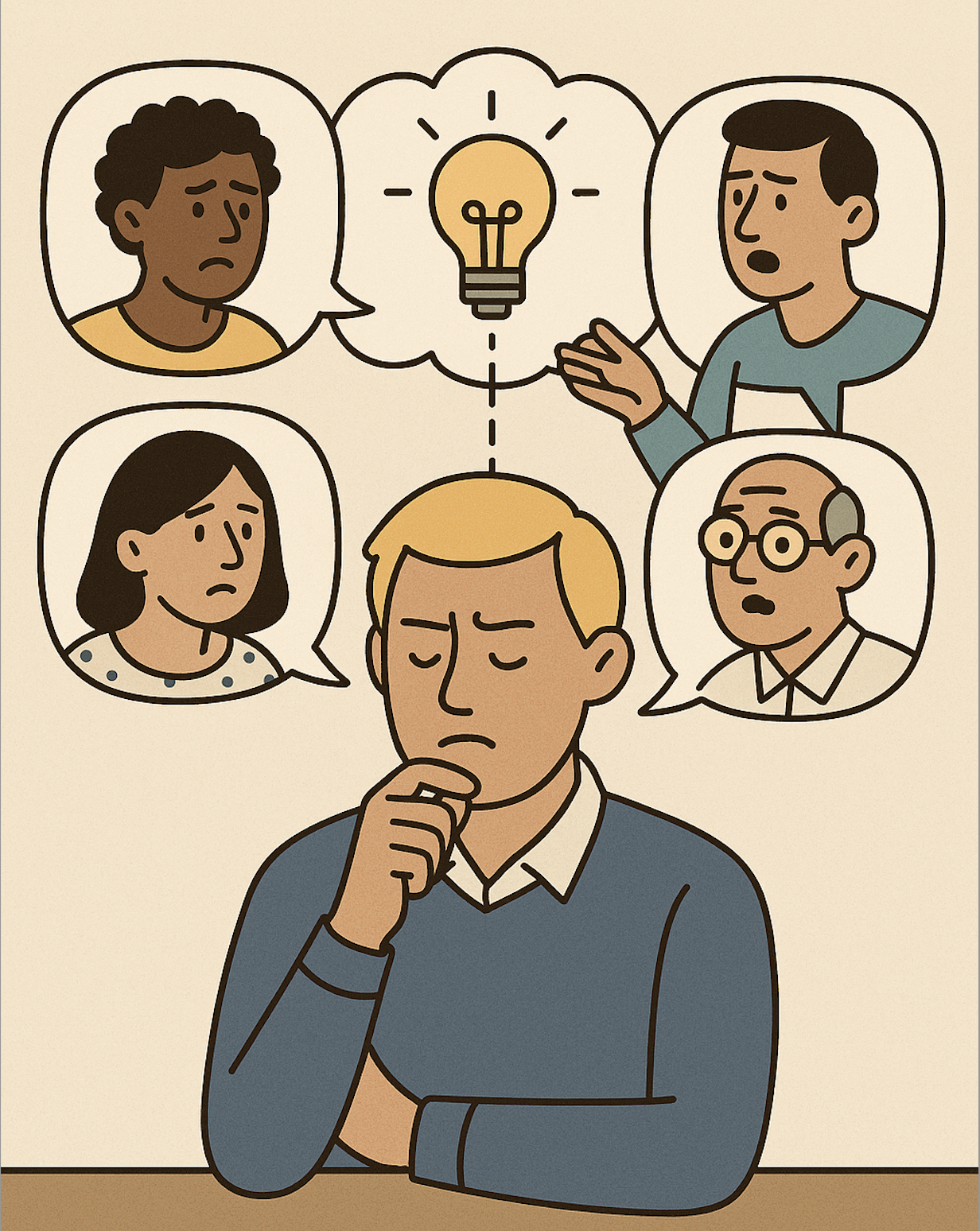

So how does this realization translate to the way I approach product management? Well first, I’ve accepted the fact that despite my best efforts to capture everybody’s feedback, some people will stay unhappy no matter what I give them (but I keep trying of course!). Second, I make it a point to listen to as many people as I can. I’m over the economic generalizing and assuming that just because one person does things a certain way, that means everyone else does too. Once I talk to as many people as I can, I can narrow down the core problem. If I can’t, then that just means I haven’t talked to enough people (or there isn’t a problem, which is rare). And third, I iterate. A lot. At every step of the way.